UKAEL Annual Lecture, 16 December 2015

Edmund J Safra Theatre, King’s College London

BREXIT: PROCESS, SUBSTANCE AND CONSEQUENCE

Paul Craig*

It is a pleasure to have been asked to deliver this year’s UK Association of European law lecture. I was offered a choice of topics by the distinguished chairman, who nonetheless also suggested that something on Brexit would probably draw the crowds in. The next two years will indeed be important for the future of UK, it is not going too far to say that the referendum will define our relationship with the EU and have profound consequences for the unity of the UK. The ensuing lecture is divided into four parts. The first considers the background issues that have shaped the process leading to the referendum. This is followed by consideration of the substantive issues placed on the negotiating table by the Prime Minister in the Chatham House speech in November 2015. The last two parts address the consequences of a no vote on the UK’s relationship with the EU, and on the future of the UK.

1 Process

There are two dimensions to the process leading to the UK referendum that must be disaggregated. First, the referendum is predicated on assumptions as to the institutional malaise that is said to beset the EU. Secondly, the referendum is also predicated on assumptions concerning the substantive power that is wielded by the EU and whether this is warranted. There is, as will be seen, an important thread of constitutional responsibility that runs through both dimensions of process.

(a) The Status Quo: Institutional Assumptions

The discourse concerning the UK referendum is conducted explicitly against the status quo, and implicitly against assumptions concerning ascription of responsibility for the existing schema. The framing of the issue results from the elision of both dimensions. Thus the ills of the EU are conceived to be the responsibility of the EU, conceived in this respect primarily to be the Commission, together with other ‘powers’ in Brussels. It follows that it is the bounden duty of national governments to renegotiate the Treaty if possible to remove the malaise thus created. It’s a great story, save for the fact that it bears little relation to reality. The central flaw resides in the implicit assumption that grounds the argument, which is like many such assumptions a good deal less secure than might initially be thought.

Consider the inter-institutional division of power within the EU. The discourse on this issue commonly includes that of democracy deficit and its implications for EU political accountability. The financial crisis unsurprisingly brought back to the fore concerns about the very design of the EU’s institutional structure and issues of democracy deficit, on which there is already an extensive literature. There is no intent to traverse the arguments concerning democracy deficit in detail again here. Suffice it to say that the disjunction between power and electoral accountability is the most potent aspect of the democracy deficit argument. Power is dispersed between the Commission, European Parliament, Council and European Council. The EP is the only institution that is directly elected, although after the 2015 EP elections the Commission President has electoral credentials. The fact remains that the voters have no ready way of achieving policy change through the ballot box, since modification in the composition of the EP will not necessarily lead to any direct shift in the substance of EU policy, given the power over the legislative process wielded by the Council, European Council and Commission.

There is, however, a dearth of literature concerning constitutional responsibility of Member States for the status quo. Consideration of the causal influences underpinning Treaty reform has not been matched by attendant analysis of what this should be taken to connote in terms of the constitutional responsibility of Member States for the resultant institutional architecture. This is a serious failing. The democracy deficit critique is presented as a critique of the EU. It is the EU qua real and reified entity that suffers from this infirmity, the corollary being that blame is cast on it. The EU is of course not blameless in this respect, but nor are the Member States, viewed collectively and individually.

The present disposition of EU institutional power is the result of successive Treaties in which the principal players have been the Member States. There may well be debate as to the relative degree of power wielded by Member States and the EU institutions in the shaping and application of EU legislation, but there is greater consensus on the fact that Member States dominate at times of Treaty reform. The inter-institutional distribution of power is the result of hard fought battles, the results of which are embodied in Treaty amendment. Thus insofar as the present arrangements divide EU policymaking de facto and de jure between the Commission, Council, European Parliament and European Council, this is reflective of power balances that the Member States were willing to accept. This is readily apparent when considering the initial Rome Treaty and any of the five major Treaty reforms since then. It is powerfully exemplified by the debates concerning institutional reforms in the Constitutional Treaty, which were then taken over into the Lisbon Treaty. It was evident most notably in the battle as to whether the EU should have a single President who would be located in the Commission, or whether a reinforced European Council should also have a long-term President. It was apparent in the debates as to Council configurations, and who would chair them. It was the frame within which the discourse took place concerning the number of Commissioners and the method of choosing them.

It would not be difficult to devise an EU institutional and decision-making structure that would address the democratic deficit as adumbrated above. It would be possible to have a regime in which the people voted directly for two constituent parts of the legislature, the European Parliament and Council, and for the President of the Commission and the President of the European Council. It would be possible in theory to have the previous package, but only a single elected President for the EU as whole. The political reality is that radical change of this kind has not happened because the Member States were unwilling to accept such a disposition of power. It is true that the choice between two Presidents and a single President for the EU was debated during the negotiations leading to the Constitutional Treaty. It is equally true that discourse concerning the election of the Commission President began in the 1980s. It should nonetheless be recognised that the broader reforms set out above were not on the political agenda during the extensive negotiations concerning institutional power in 2003–2004 that led to the Constitutional Treaty, nor in the subsequent discussions that culminated in the Lisbon Treaty. Even if the broader package of reforms were adopted it could not ensure that the people would exercise electoral control over the direction of EU policy, since the European Council would still be populated by Heads of State, who would continue to have a marked influence over the policy agenda, and members of the Commission, with diverse political views, would still be chosen by the Member States.

There is moreover a constitutional paradox lurking here. The diminution of state power in the Council and European Council that would be entailed by change of the kind mooted above would probably not be constitutionally tolerated in some countries and would lead to the charge that the EU was truly becoming a super-state. Thus while the German Federal Constitutional Court has repeatedly chided the EU in relation to its democratic credentials, it would likely be one of the national constitutional courts to decide that an institutional configuration of the kind set out above that addressed the democratic deficit as presently understood would not be compatible with German constitutional law. This was because such a change would mean that the EU was moving closer to a federal state, with the consequence that the Member States could no longer be regarded as the Masters of the Treaty in the manner hitherto. The same sentiment would likely be voiced by some within the UK, albeit from a more overtly political perspective. Thus while the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee has oft-criticised the EU for its democratic shortcomings, it would not view with equanimity institutional architecture of the kind adumbrated in the preceding paragraph, since it would be regarded as increasing the EU’s legitimacy at the expense, inter alia, of national parliaments.

It may serve national governments, including that of the UK, to blame the EU for institutional failings that reside in choices made repeatedly by the Member States themselves. This dereliction of national constitutional responsibility has, however, important consequences, notably in this context the increased difficulty in convincing voters as to the merits of the institution thus created, more especially so at a time when membership is on the line.

(b) The Status Quo: Substantive Dimensions

The focus now shifts to the substantive assumptions underlying the referendum process. The logic of renegotiation is that some things should change. It is exemplified most powerfully by the claim that the EU has power that it should not have, or does not need. This is the substantive assumption underlying the renegotiation process. It is the Eurosceptic position as will be seen below. In the months after the Prime Minister’s Bloomberg speech in which he promised the referendum there was, however, much speculation as to the precise subject matter that would form the basis of this renegotiation. David Cameron in that speech gave scant indication of what he would bring to the negotiating table, other than that there were serious things that needed to be improved in the modus operandi of the EU. The issues for renegotiation only became clearer in the Chatham House speech in 2015, to which we shall return in due course. There are nonetheless two fundamental points to be mindful of concerning the scope of existing EU power.

First, we need to understand why the EU has its current range of power. Discourse over EU competence has been influenced by parallel concerns as to those that shaped debate about EU institutions. Thus for some the shift in power upward towards the EU is the result primarily of some unwarranted arrogation of power by the EU to the detriment of states’ rights, which subsidiarity has been powerless to prevent. This is to say the very least an over simplistic view of how and why the EU has acquired its current range of power. The reality is that the scope of EU power has always been the result of three factors: the attribution of new competences through successive Treaty amendments; regulations and directives enacted pursuant to these Treaty provisions in accord with the EU legislative procedure; and judicial interpretation of the Treaty provisions and legislation. There is room for some disagreement concerning the relative weight ascribed to these three variables. The reality is nonetheless that it has been the Member States that decided after extensive discussion within Inter-Governmental Conferences leading to Treaty revisions to accord the EU competence in new areas. The legislation enacted pursuant to these provisions has always required consent from the Council representing Member States interests, and post-1986 much has also received the EP’s imprimatur. The crude picture of a smash and grab operation by the EU institutions or the EU courts belies reality.

Secondly, this still leaves assessment as to whether current EU competence as embodied in the Treaty provisions and legislation made pursuant thereto, is set at the right level, and its impact on the UK. We do not have to speculate about this in abstract, since we have the benefit of the balance of competence review. This was established in 2012. It is the most comprehensive review of EU competence undertaken by any Member State. The object was to assess the impact of EU law broadly conceived on all areas of government action. To this end each government department considered the effect of EU law on its area.

There is little doubt that the review was launched with the hope in some quarters that it would provide the substance for subsequent renegotiation of the Treaties. The government would then have the ammunition to take to the bargaining table, whereby it could claim that the UK had carried out an unimpeachable, detailed inquiry that revealed the excess of EU competence. Matters turned out rather differently. The inquiry conducted by government departments was indeed unimpeachable in terms of process, and well-judged in terms of substance, but it did not produce the ammunition that the Eurosceptics had hoped for. All of which goes to show that the best laid plans often go off the tracks.

In terms of process, it showed the UK civil service at its very best. It was told to conduct the review and did so. The civil service was, however, determined to ensure that the outcome would withstand serious scrutiny. It was not about to sully its reputation by authoring reports that might be regarded as politically biased. The process was therefore unimpeachable and uniform throughout. The lead department for the particular topic engaged in broad consultation. This took the form of publicising the review process; receiving written consultations; undertaking town-hall type meetings; and soliciting views of experts in day long discussions held in the department with those responsible for the study. The lead department produced a draft report based on the results of the consultation, including research that it had done. This draft report was then subject to rigorous scrutiny in a face to face meeting with a team from the Cabinet Office, which would test its compatibility against the evidence. This team was reinforced by two ‘external challengers’. They were, as the title suggests, people from outside government with expertise in the area, who brought a critical eye to the draft report. The external challengers often had very different views concerning the EU, and there was therefore no necessary commonality between them. It was only after this process that the report was submitted to ministers for approval, which was generally given, the exception being the report on free movement that was subject to lengthy delays in the Home Office.

In terms of substance, the reports generally found that EU competence was pitched at about the right level. There were, as might be expected, questions about the wisdom of particular legislative initiatives, but that would inevitably be so in the context of a review into any area where a public authority wielded power, whether at national or EU level. The bottom line was that the Eurosceptics did not get the ammunition that they had hoped for from the review. While the civil service was instructed not to draw direct conclusions from the material, it is nonetheless clear from the reports that the general inference was that the distribution of competence was about right and that membership on these terms was beneficial to the UK. This was not lost on commentators. In a previous era it might have been possible to bury a report that did not cohere with what the government intended, although it would have been difficult to do that with a report of this size. The reality is that we live in an internet age, with the consequence that interring unwelcome reports produced after public input is simply not an option. There is no putting this particular genie back in the bottle. The reports have become known throughout the EU, not only in academic circles, but also among the political establishment in Member State capitals and in Brussels. It is of course open to the government to contradict its own review on a particular topic, but this would be doubly difficult, in part because it signed off the review and in part because it would have to adduce convincing evidence as to why the detailed departmental assessment was to be doubted.

The difficulties for the government in deciding what to renegotiate are cast into sharp relief by the balance of competence review, which is in part why the Prime Minister was so unforthcoming about this until November 2015. These difficulties were further exacerbated by the fact that the Prime Minister sought a renegotiating strategy that would blunt the edge of a UKIP challenge, and satisfy its Eurosceptic members. We know what UKIP desires, which is exit from the EU. The best guide to the aspirations of the Eurosceptics is the manifesto of Fresh Start, a cross-party group with the objective of recasting the UK’s relationship with the EU, although predominantly a vehicle for Conservative Party Eurosceptics. It produced a Manifesto for Change, A New Vision for the UK in Europe in January 2013. The manifesto listed five principal changes to the existing Treaties: an emergency brake for any Member State regarding future EU legislation that affects financial services; repatriation of competence in the area of social and employment law to Member States; an opt-out for the UK from all existing EU policing and criminal justice measures not already covered by the Lisbon Treaty block opt-out; a new legal safeguard for the single market to ensure that there is no discrimination against non-Eurozone member interests; and the abolition of the Strasbourg seat of the EP. This was just the tip of the iceberg, since Fresh Start also sought a plethora of other changes, which were said to be attainable within the framework of the existing Treaties. Fresh Start published a shortened and revised version of its manifesto in November 2013, which included proposed Treaty amendment, and change within the existing Treaty fabric. The list was much the same as in the earlier document, but there were additional demands which included: a UK opt-out from the EU Charter of Rights; the introduction of red cards for national parliaments, for existing and future legislation; a general emergency brake akin to the Luxembourg compromise that a Member State could use if EU legislation enacted by qualified majority affected its fundamental interest; and the ability to amend legislation speedily in the light of ‘perverse’ ECJ judgments.

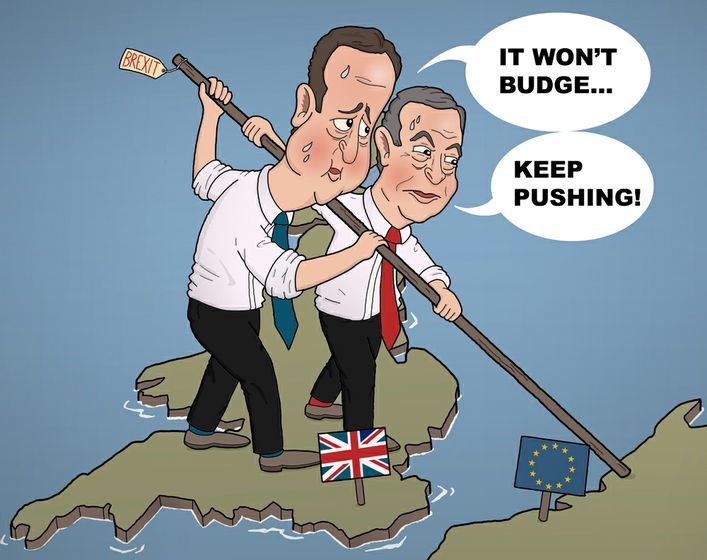

The Conservative leadership was thus caught between a rock and a hard place. If the Prime Minister sought seriously to address the agenda of his Eurosceptics he would enter negotiations playing a hand that was destined to fail. If he played a moderate hand he risked entering a bargaining forum in which he was destined to disappoint this powerful group. This tension was forcefully exemplified by the reception accorded to the Prime Minister’s initiative in October 2014, when he finally placed something concrete on the bargaining table, viz quantitative limits to the free movement of persons. The reaction was swift and predictable from the EU institutions and Member States, which emphasised the centrality of free movement to the EU, with the corollary that it was not up for grabs.

We now know what is on the bargaining table and will consider this below. It is nonetheless important not to lose sight of the important point of constitutional principle that should inform the referendum process. Renegotiation provides the window for constitutional voice. The government exercises voice on behalf of its people, not just those who voted for it. It is there to represent the public interest, not just its own particular vision. To be sure the government of the day may well have a view as to what constitutes the public interest on a particular issue. This is entirely legitimate and part of the very raison d’etre of government. It does not however alter the point being made here. The government exercises voice on behalf of the people when engaged in renegotiation of the UK’s treaty obligations, and must do so responsibly.

This connotes a constitutional obligation to present the case in relation to the EU in an even handed manner, notwithstanding the fact that this might not be agreeable to those with Eurosceptic leanings. This in turn should oblige the government to be open about the results of the balance of competence review. The discourse concerning the terms on which to renegotiate has been conducted without reference to the fact that the most far-reaching review conducted by the UK government reached the conclusion that the balance of EU competence was generally correct and beneficial to the UK. The general public should surely be told this, and it is part of the government’s constitutional responsibility to do so. The reality is to the contrary, the Conservative Party downplayed the results of the review and gave them the least possible publicity. The review was treated akin to Banquo’s ghost, something that should be ignored in the hope that it would go away. Most ordinary UK citizens have no idea that the review exists, or its findings. This is quite wrong. One can but imagine the demands of the Eurosceptics for summary publication of this material if the substantive conclusions had inclined in their direction. Prominent members of the European Scrutiny Committee would assuredly have framed this in terms of high constitutional principle. They would have been right to do so. It is axiomatic that the constitutional principle does not alter, or cease to be applicable, just because the substantive conclusions reached by the review are less attractive for those of Eurosceptic persuasion.

2 Substance

The Prime Minister finally unveiled the UK’s negotiating position on November 10 2015, which consists of four parts.

First, there should be protection for countries outside the Eurozone. This was required in order to: protect the single market and ensure that all twenty eight Member States decided its rules; to prevent discrimination against non-Eurozone countries; and to ensure that non-Eurozone countries did not have to shoulder additional costs from integration of the Eurozone. The Prime Minister asked European leaders to agree clear and binding principles that would protect non-Euro countries, and a safeguard mechanism to ensure that those principles were respected and enforced.

Secondly, there should be increased emphasis on competitiveness and the cutting of red tape, thereby removing unwarranted regulatory burdens on industry, the idea being that competitiveness should be written in the DNA of the EU.

Thirdly, there should be change that impacted on sovereignty and subsidiarity. Thus the Treaty commitment to ever closer Union should no longer apply to Britain. For the Prime Minister this meant a clear, legally binding and irreversible agreement to end Britain’s obligation to work towards an ever closer union. There should in addition be some red card regime, such that if a certain number of national parliaments objected to a measure it could be prevented from becoming law, and there should also be greater emphasis on the application of the concept of subsidiarity.

The fourth and final part of the renegotiation package concerned free movement and immigration. The Prime Minister did not press for change to the basic right of free movement, acknowledging that it was a key part of the single market. He nonetheless sought change that would prevent what he termed abuse of the right to free movement, and facilitate greater control over migration in line with the Conservative manifesto. This meant ensuring that when new countries acceded to the EU free movement would not apply until their economies converged much more closely with existing member states and dealing with abuse of free movement. EU migrants should moreover have to live in the UK and contribute for four years before they qualified for in-work benefits or social housing, and the practice of sending child benefit overseas should cease. The Prime Minister was cognizant that such changes could pose difficulties for other Member States, and said that he was open to different ways of dealing with them, while insisting that the basic demands should nonetheless be met. This sentiment was reiterated on the eve of the European Council meeting in December 2015, since it had become clear that there was resistance to this UK demands from other Member States.

The renegotiating package can be analyzed both legally and politically. Space precludes detailed consideration here, but some flavour of both dimensions can be proffered.

In legal terms, it is clear that some demands will be easier to meet than others. Thus, the second set of demands that seek reduction in EU red tape is pushing at an open door. There may of course be differences of view as to the line between red tape and valuable regulation, but that is inevitable and will not prevent an agreement being brokered. By way of contrast the fourth demand, changes to benefits for EU migrants, particularly those in work, raises complex legal issues and there is likely to be significant political opposition. We should not however forget in this respect that EU law merely demands that we do not discriminate in the benefits given to those in the UK and those entering from the EU. The EU does not impose any particular level of benefit.

The third demand for extra red card powers for national parliaments will probably gain approval from the other Member States, but will arguably require Treaty amendment for it to take effect. The other limb of this demand, viz an end to ever closer union at least as it applies to the UK will also probably be met, although the precise legal modality remains to be seen, the options including Treaty amendment, a Protocol specific to the UK, or a decision by the heads of state that would constitute an interpretation of the relevant phrase that would be binding in international law.

This leaves the first category within the renegotiation package, which concerns different aspects of economic governance. The general feeling appears to be that, given sufficient political will, the skills of the legal draftsmen will ensure that legal provisions can be crafted to meet the particular concerns listed in this part of the PM’s letter. This may well be so, but the scale of the undertaking should not be underestimated. Take but one limb from within this category, the demand that non-euro area Member States should be protected against the possible adverse impact of measures devised for the euro area states crafted as they are within the specific institutional contours of the Eurogroup and Euro Area Summits. The assumption is that an emergency brake could be devised to meet the UK’s concerns, by way of analogy with the procedure that operates within Articles 82 and 83 TFEU. There are three related aspects to this procedure: there is the subject-matter to which the brake can be applied, which in the context of, for example, Article 83 is a criminal law draft directive; there is the trigger for its deployment, viz, that the proposed law would affect fundamental aspects of its criminal justice system; and there is the possibility in the absence of consensus reached in the European Council that some states can proceed with the measure through the enhanced cooperation procedure.

The application of these component elements to the sphere of economic governance is not straightforward. The subject matter to which the brake would be applicable would be very much broader than in Articles 82 and 83 TFEU. It would have to embrace any measure that impacted on the single market. This would in itself involve difficult definitional issues: any measure made pursuant to Part 3 of the TFEU could have this impact, and it might well be difficult to have a narrower definition without thereby creating formalistic definitional problems. The trigger for use of such a brake would have to be devised. The criterion in Articles 82 and 83 may be abstract, effect on a fundamental aspect of the criminal justice system, but the aim is nonetheless reasonably clear. It would be considerably more difficult to frame the criterion for an emergency brake in relation to internal market measures. Consider the following possibilities. The trigger for reconsideration of a draft internal market directive could be cast in terms of serious adverse impact on non-euro states; it could be framed in terms of discrimination against such states; or it could be defined in terms of an effect on a fundamental aspect of a Member State’s economic ordering. This does not exhaust the possibilities, but it is readily apparent that the tests are very different. There are moreover difficulties with the third component of the emergency brake procedure, the possibility for states to use the enhanced cooperation procedure. This might be thought to be unobjectionable if the emergency brake were applied to the internal market. It might indeed be contended that this would fit neatly with the desire for differentiated integration. The matter is not so simple. To the contrary, the use of enhanced cooperation in this context might run counter to the very rationale for use of the emergency brake. The reason is not hard to divine. If non-euro states wish to use an emergency brake because they object to a draft internal market directive on the ground that it is ‘biased’ towards euro area states, then they might be content for the enhanced cooperation procedure to be used, thereby allowing differentiated integration in the relevant area. They are however likely to take the contrary view if the impact of the relevant measure cannot de facto be hermetically confined to the euro area states. This would in turn generate ‘nice’ questions as to whether the criteria for the enhanced cooperation procedure would be satisfied in such circumstances.

In political and indeed literary terms the Chatham House letter and subsequent missive to the European Council President are also interesting. Both are quintessentially political documents, the core content of which is the same, but with differences around the periphery. They are addressed to more than one audience. Thus aspects of the Chatham House letter are written for members of the Prime Minister’s own party, as exemplified by the material within the third part of the renegotiation package, which concerns EU competence over human rights, in which he seeks to reassure his MPs that the EU Charter of Rights would not be allowed to stand in the way of the UK’s renegotiation of its relationship with the Council of Europe and the ECHR, nor would it be allowed to impede enactment of a UK Bill of Rights to replace the HRA. The Prime Minister is addressing the same audience when expressing affinity to the kind of ultra vires and identity locks used by the German Federal Constitutional Court. By way of contrast the general UK public is the intended audience of the Prime Minister’s remarks concerning the economic and security benefits of staying in the EU. A third audience is the EU Member States, and here we should not allow the detail to mask the headline issue, which is that while the Prime Minister carried through on his promise to hold a referendum, the demands are mild compared to those sought by the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative party. The Prime Minister knew that a wish list akin to that in the Fresh Start manifesto could never be attained. It is moreover very doubtful whether the authors of Fresh Start ever thought that it could be; it was in reality merely a stepping stone towards their campaign for exit.

3 Consequences: The Relationship with the EU

If the referendum results in a no vote, this will signal the UK’s exit from the EU, assuming that there is no post-referendum new deal offering something that might incline UK voters to change their mind. Some of what happens thereafter is predictable, some is not.

The immediate aftermath is predictable insofar as the Lisbon Treaty contains provisions on exit that had not existed hitherto. Article 50 TEU provides that any Member State may decide to withdraw from the EU in accordance with its own constitutional requirements. It must inform the European Council of its intention to do so. The EU then negotiates and concludes an agreement with the state, in the light of guidelines provided by the European Council, which sets out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union.

The agreement is made in accordance with Article 218(3) TFEU, with the consequence that it is concluded on behalf of the EU by the Council, acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament. The Treaties cease to apply to the withdrawing state from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification by the state of its intent to withdraw, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period. The state seeking to withdraw does not participate in the discussions or decisions in the European Council or Council concerning it, and its vote is therefore not taken into account when calculating a qualified majority. If a State that has withdrawn from the EU seeks to re-join, it must go through the procedure in Article 49 TEU concerning entry of new states.

All of the above will therefore take time. Those that imagined that exit will lead to a speedy repatriation of all competences to the UK should therefore adjust their time horizons. It is not going to happen fast. This is quite apart from the fact that many areas of UK law are wholly enmeshed with EU law. The unravelling exercise will take many years to complete. It will be for the UK government to decide whether it wishes to alter the relevant laws on a particular topic, given that it is no longer bound to their particular content by reason of EU membership. Put crudely the answer may be yes in some instances, no in others, or what is more likely in many instances is that there will be a via media whereby some of the content is retained because it is accepted, and some is altered. These choices will, moreover, often be markedly constrained by external forces in the manner set out below.

The very fact that the unravelling exercise via Article 50 TEU would take time has led some Eurosceptics to speculate about the possibility of repealing the European Communities Act 1972 immediately after a no vote in the referendum. The government appears to have discounted this possibility, stating that it would use the Treaty machinery in Article 50. This is assuredly wise, both legally and politically. The ‘ECA repeal option’ would be problematic legally. It would be viewed as an insult politically by the EU and its Member States, and as economists would properly remind us there is no such thing as a free insult, with payback coming swiftly when the UK has to negotiate with the EU on a plethora of issues.

What is less readily predictable is the legal nature of relations between the UK and the EU thereafter. The principal options are joining the European Economic Area, as in the case of Norway; negotiating a series of free trade agreements, as in the case of Switzerland; or negotiating a new customs union relationship with the EU, as in the case of Turkey. The Prime Minister in his Bloomberg speech rejected all three options. So too did the framers of the Fresh Start Manifesto, who concluded that such arrangements whereby the UK would be bound by trading rules in relation to which they had no input would be a ‘disastrous position for the UK in terms of services trade’. The Prime Minister reiterated his scepticism about such options in his Chatham House speech, when he set out the terms of the UK renegotiation package.

There are good reasons for rejecting these options, but it does rather beg the question as to the nature of the future relationship between the EU and the UK. The negative reaction to the principal options is not matched by indication of a positive alternative. The implicit thinking seems to be either that some ad hoc deal will be put together between the EU and the UK, or that the UK will simply operate as a country outside the EU, trading with it in the same manner as most other countries in the world. The terms of any ad hoc deal between the UK and the EU cannot be predicted in advance, save for the fact that the other Member States will not come close to signing up to a deal whereby the UK secures the economic benefits of the single market without subscribing to the social obligations incumbent on other EU Member States.

This leaves the alternative option, viz the UK simply subsists as a country outside the EU, trading with it in the same manner as many other countries. This is certainly an option, but the assumption that we will thereby be free from EU rules relating to trade or indeed some other matters is a serious non-sequitur. The UK will continue to be bound by some of these provisions, either because the EU demands, for example, certain safety standards for all goods sold in the EU, or because the EU regulatory provisions have themselves been incorporated into global regulatory standards that thereby bind the UK wherever it trades. The UKIP vision of a UK freed from the EU, whereby all powers revert to the autonomous control of the nation state, is just that, a vision that bears no relation to reality.

4 Consequences: The Impact on the UK

The consequences of a negative vote in the referendum could indeed be even more dramatic, since as many commentators have pointed out it could well lead to the break-up of the UK. If, as is likely, a majority of those in Scotland vote to remain in the EU, this will trigger a renewed call for a Scottish independence referendum, and it is quite likely that the SNP will win. The decision to leave the EU could therefore mean an end to two unions not just one. Scotland will apply for EU membership and will secure this. The Catalonian-type objection that was raised on the last occasion will be moot, since the remainder of the UK will have left the EU. The preceding scenario is not fanciful. It is highly likely. It begs two concluding thoughts, which link back to points made earlier.

First, we have to ask seriously whether the four points on the bargaining table really are worth this outcome. Thus even if we fail to secure all such demands do we seriously think that we should leave the EU because we cannot secure the desired deal on worker benefits? This is more especially so given the evidence that the UK benefits economically from EU migration, and even more so given the economic and social benefits that the UK derives from EU membership, as attested to by the competence review.

Secondly, in answering the preceding question reflect also on the fact that the economic consequences of EU exit, break-up of the UK and Scotland becoming an EU member are likely to be severe, dwarfing any sums at stake in the payment of EU benefits to migrant workers. The reason is not hard to divine. Firms seeking access to the EU will locate in Scotland, or shift their location to Scotland, more especially if there is an extended period of uncertainty concerning the UK’s relationship with the EU.

* Professor of Law, St John’s College, Oxford. This lecture draws on my chapter entitled ‘Responsibility, Voice and Exit: Britain Alone?’ in Patrick J. Birkinshaw and Andrea Biondi (eds), Britain Alone! The Implications and Consequences of United Kingdom Exit from the EU (Kluwer Law International, 2016).